This is probably going to be the final post of the year, so I feel compelled to do one of those yearly wrap-ups that never say anything about anything. Sorry.

Let’s just clear it out now: here’s how 2009 disappointed me, how it thrilled me, and what I’m looking forward to in 2010.

In 2009 I was disappointed, irritated, or pissed off by…

-Video Game journalism, which hit new depths of unwarranted self-importance, and completely sapped any meaning out of the term “hardcore gamer.”

-3-D movies. 3-D effects still don’t add anything to the experience of watching a movie, and those glasses look incredibly stupid and probably aren’t hygienic. 3-D was once the height of kitsch. Why are we taking it seriously now?

-The cult DVD market implosion. 2009 saw the possibility of bankruptcy for Image Entertainment, Dark Sky films ending their retro film line, and the complete demise of ADV, BCI, and Fusian. It was ugly.

-Bioware. Between their stupid trailer for Dragon Age and “David Gaider -- Novelist,” I’m starting to hate them in spite of their mostly competent game design.

-Celebrity deaths.

-Real life. It was a terrible year IRL.

But to be fair, in 2009 I was thrilled, delighted and contented by…

-Dungeon crawlers. After playing Etrian Odyssey 2 earlier this year, I went on a bender with the original Etrian Odyssey, The Dark Spire, Deep Labyrinth, and Shin Megami Tensei: Devil Survivor. I expect to grab Class of Heroes for the PSP soon.

-The DS, which is easily the must-own platform for this hardware generation. Aside from playing host to all of the games listed above (besides Class of Heroes), the DS also received 7th Dragon (in Japan, at least), Phantasy Star 0, Nostalgia, and an English release of Retro Game Challenge to go along with its already stellar library of games I actually play.

-Vantage Master! Falcom offers this awesome strategy game on their website, in English, free of charge!

-Mondo Macabro’s releases of The Warrior (Jaka Sembung) and Born of Fire.

-My expanding collection of martial arts movies. Of the thirty-five movies I reviewed this year, twenty-three were kung fu movies and seventeen of those were acquired in 2009, including obscure crap like Child of Peach and War of the Wizards. Go me.

-Ashes of Time Redux didn’t suck. Thanks Wong Kar Wai.

-Snus: Wonderful Swedish tobacco.

Last year, I got very drunk on New Year’s and made out with a strange woman at a party where I didn’t know anybody. As my friend Pilgrim was driving me home, I had one of those awful moments of clarity that one typically drinks to avoid, and expressed some regret that the first day of the New Year would be spent nursing a bitchin’ hangover. “Look at it this way: you have an entire year to make up for it.” That was his almost brain-bendingly optimistic response.

In similar spirit, here’s what I’m looking forward to in 2010:

-Falcom games on the PSP in English -- the PSP already boasts Ys 6 and Gurumin, but a recent announcement shows that Falcom wants to license more games for English language release. Considering Ys 7 just came out this year in Japan (and looks way better than 6) I couldn’t be more stoked. Other possible releases include Zwei! and Brandish: Dark Revenant. 2010 could be a nice year.

-A new Gene Wolfe novel, The Sorcerer’s House, is scheduled for release on March 16.

-Maybe -- possibly -- hopefully -- but doubtfully, Tsui Hark’s upcoming Di Renjie won’t suck.

-Let’s hope Magnolia’s dvd for Red Cliff is more sensible than their condensed theatrical version.

The first full year of actual, consistent blogging has been great fun. Thanks to the three people who actually bothered to consistently read it. See you guys next year.

12/30/09

12/28/09

Game Review -- Kyonshi 2/キョンシーズ2

Hello Dracula wasn’t just popular in Taiwan. The mix of the macabre silliness and cute, kung fu fighting kids won over Japanese audiences when the first few movies were adapted into a television series that aired in the late eighties. It was popular enough to spawn toys and a manga by an artist named Yu Hiroe. The most curious artifact of its popularity in Japan? A Famicom game from Hudson!

Hello Dracula wasn’t just popular in Taiwan. The mix of the macabre silliness and cute, kung fu fighting kids won over Japanese audiences when the first few movies were adapted into a television series that aired in the late eighties. It was popular enough to spawn toys and a manga by an artist named Yu Hiroe. The most curious artifact of its popularity in Japan? A Famicom game from Hudson!A first look at it might fool you into thinking Kyonshi 2 shamelessly plagiarizes Dragon Quest, but it’s actually closer to Zelda 2. The goal -- so far as I can tell without any knowledge of Japanese -- is to collect the various jiang-shi zombies scattered about town and return them to the Taoist temple, where Ten-ten awaits to issue orders and generally be a bossy little bitch.

You pick from the four male characters (you can’t play as Grandpa King) at the start screen, although I can’t tell what makes them different, and then you’re free to roam about town, buying and selling stuff and going on fetch quests for the locals. Eventually, you’ll walk into a location where the corpses are hanging out, and then you’ll be in the Zelda 2 side-scrolling mode. A button punches, B button kicks, and jumping is assigned to the up key on the d-pad. It’s an awful layout that doesn’t really affect anything since the enemies hop at your character in a single, unchanging pattern. They have high hp, so hitting them over and over until they die becomes tedious pretty fast.

You pick from the four male characters (you can’t play as Grandpa King) at the start screen, although I can’t tell what makes them different, and then you’re free to roam about town, buying and selling stuff and going on fetch quests for the locals. Eventually, you’ll walk into a location where the corpses are hanging out, and then you’ll be in the Zelda 2 side-scrolling mode. A button punches, B button kicks, and jumping is assigned to the up key on the d-pad. It’s an awful layout that doesn’t really affect anything since the enemies hop at your character in a single, unchanging pattern. They have high hp, so hitting them over and over until they die becomes tedious pretty fast. And for those that don’t know Japanese, the frustrating part will come when the battle is over, and leaving the battle screen shows that there are no reanimated corpses following as they guide their character back to the temple. The player needs to buy Taoist charms before the zombies will hop behind him or her. And it’s not a simple task either, since there are a couple dozen characters to talk to who will give you advice, or sell you items, or serve some other purpose I couldn’t discern. And in order to get certain items, the player has to speak to certain characters while holding other items that must be found the same way.

And for those that don’t know Japanese, the frustrating part will come when the battle is over, and leaving the battle screen shows that there are no reanimated corpses following as they guide their character back to the temple. The player needs to buy Taoist charms before the zombies will hop behind him or her. And it’s not a simple task either, since there are a couple dozen characters to talk to who will give you advice, or sell you items, or serve some other purpose I couldn’t discern. And in order to get certain items, the player has to speak to certain characters while holding other items that must be found the same way. A lot of Famicom RPGs are opaque in this way, particularly the ones that didn’t copy Dragon Quest by the numbers. Adding tedious combat sequences makes Kyonshi 2 even more irritating than other pseudo-RPGs of the era, somehow playing into the long-held stereotype of licensed video games held in the United States -- borderline unplayable.

A lot of Famicom RPGs are opaque in this way, particularly the ones that didn’t copy Dragon Quest by the numbers. Adding tedious combat sequences makes Kyonshi 2 even more irritating than other pseudo-RPGs of the era, somehow playing into the long-held stereotype of licensed video games held in the United States -- borderline unplayable.Stuff of interest:

12/27/09

Hello Dracula (Chiu Ching-Hung, 1985)

[This might actually be Hello Dracula 2. Please forgive my ignorance in reviewing this film as the first in the series if it is. Thank you.]

The first in probably the longest running series of fantasy films during Taiwan’s infatuation with the genre during the eighties, Hello Dracula (aka 幽幻道士, Son of Chinese Vampire and Corpse Boy) receives very little attention here in the west, even among cult movie aficionados. It’s generally known only to die-hard kung fu movie fans, and even then, it isn’t widely discussed online, possibly because of the limited availability of both the original film and its sequels. (Granted, I probably just jinxed it and all six movies will end up on edonkey tomorrow morning, and yes, there are six) Of the many jiang-shi (or gyonshi/kyonsi) movies that came in the wake of Mr. Vampire (Ricky Lau, 1985) this is my favorite.

The first in probably the longest running series of fantasy films during Taiwan’s infatuation with the genre during the eighties, Hello Dracula (aka 幽幻道士, Son of Chinese Vampire and Corpse Boy) receives very little attention here in the west, even among cult movie aficionados. It’s generally known only to die-hard kung fu movie fans, and even then, it isn’t widely discussed online, possibly because of the limited availability of both the original film and its sequels. (Granted, I probably just jinxed it and all six movies will end up on edonkey tomorrow morning, and yes, there are six) Of the many jiang-shi (or gyonshi/kyonsi) movies that came in the wake of Mr. Vampire (Ricky Lau, 1985) this is my favorite.

For those not familiar with the “Chinese vampire/zombie” myth, it was once believed that in order for a human spirit to attain peace after death, their corporeal self should be buried in a pleasant place near their hometown. Taoists were charged with transporting corpses to their home towns, where they would be interred, and the myth of reanimated corpses that would hop along behind the magically endowed Taoist was born from this practice. There’s plenty of speculation as to why they’re so often depicted in Manchu style dress and the reasons why they detect people by smelling/feeling their breath, but that’s all rather academic. Look it up on Wikipedia.

For those not familiar with the “Chinese vampire/zombie” myth, it was once believed that in order for a human spirit to attain peace after death, their corporeal self should be buried in a pleasant place near their hometown. Taoists were charged with transporting corpses to their home towns, where they would be interred, and the myth of reanimated corpses that would hop along behind the magically endowed Taoist was born from this practice. There’s plenty of speculation as to why they’re so often depicted in Manchu style dress and the reasons why they detect people by smelling/feeling their breath, but that’s all rather academic. Look it up on Wikipedia.

Set in what one assumes is the early twentieth century, Hello Dracula begins with a travelling Taoist transporting reanimated corpses through a dark forest and is accosted by a tiny hopping corpse boy. As the Taoist is getting beaten up by the little corpse boy, another Taoist, Grandpa King, is travelling through the same forest with his granddaughter, Ten-ten, his four other young apprentices/assistants, and the corpse of their former master in tow. Grandpa tells his charges that they should keep out of the forest, because the reanimated corpse of a child haunts it. No sooner does he inform them of the child than the other Taoist and the kid-zombie come crashing into his wagon, causing the corpse of Ten-ten’s former master to reanimate. The still living humans basically run away, happy to escape with their lives.

Back in town, the locals are upset by the idea that zombies haunt the surrounding forests, and the military governor of the town, whose elder brother recently died, demands that Grandpa King keep the reanimated corpses under control. Unfortunately, his chubby assistant, Shih Kua Pih, is a bit of a bumbling doof, and causes various problems with his clumsiness. Further complicating the situation is a group of foreigners who want the corpse for some sort of experiment. The poorly translated embedded subtitles don’t make it clear if said experiment is mystical or scientific in nature, as one of the corpse thieves is at least dressed as a Catholic priest, and his female companion a nun. Neither of them acts their respective parts, what with stealing corpses and doing sexy stripteases to distract the patrolling militia men.

Back in town, the locals are upset by the idea that zombies haunt the surrounding forests, and the military governor of the town, whose elder brother recently died, demands that Grandpa King keep the reanimated corpses under control. Unfortunately, his chubby assistant, Shih Kua Pih, is a bit of a bumbling doof, and causes various problems with his clumsiness. Further complicating the situation is a group of foreigners who want the corpse for some sort of experiment. The poorly translated embedded subtitles don’t make it clear if said experiment is mystical or scientific in nature, as one of the corpse thieves is at least dressed as a Catholic priest, and his female companion a nun. Neither of them acts their respective parts, what with stealing corpses and doing sexy stripteases to distract the patrolling militia men.

The movie rambles between set-pieces. Ten-ten controls the corpses with a cute song-and-dance routine; the kid-zombie plays baseball with himself; there’s a comedy vignette with the male Taoist apprentices fighting over Ten-ten’s approval. It all boils down to a climax in which Ten-ten is captured by her former master’s zombie and the corpses all get lose and run wild over the town. Mayhem ensues and the audience is served a great display of kids doing acrobatics, ritual Taoist magic and kung fu.

The movie rambles between set-pieces. Ten-ten controls the corpses with a cute song-and-dance routine; the kid-zombie plays baseball with himself; there’s a comedy vignette with the male Taoist apprentices fighting over Ten-ten’s approval. It all boils down to a climax in which Ten-ten is captured by her former master’s zombie and the corpses all get lose and run wild over the town. Mayhem ensues and the audience is served a great display of kids doing acrobatics, ritual Taoist magic and kung fu.

Liu Chih-Yu became a huge star in her role as Ten-ten, and director Chiu Ching-hung clearly chose to showcase her. As far as child stars go, she’s quite tolerable. Her male counterpart, the bumbling chubby kid Shih Kua Pih, is played by Liu Chih-han. He looks a bit older than the other kids and does pretty well with the comedy and the limited action scenes. Gam Tiu as Grandpa King pales in comparison to Lam Ching-Ying, but that comparison isn’t fair. He was a veteran Taiwanese actor and it shows in his performance. Boon Saam as the fat militia captain is quite funny.

Hello Dracula was definitely intended as a children’s film, as were many other Taiwanese fantasy movies. However, to a western viewer such as me, the sights of kids playing with corpses and little child-zombies are a bit unnerving, to say nothing of once scene where one child attempts suicide. Similarly, the Chinese attitude towards religion was always a bit different from that of the west. It feels a tad irreverent to watch a Catholic priest stealing corpses, even if he is doing so for the sake of research and is shown in a generally sympathetic light (it’s his boss that provides the white-devil stereotype). Similarly, the movie seems to have no clue that sexually objectifying a nun might offend some Christians -- unlike European nunsploitation films, where the offensiveness is part of the fun -- and one has to wonder where the Catholic priest learned kung fu. Also, animal lovers should know that animals were indeed harmed during the making of the film.

Hello Dracula was definitely intended as a children’s film, as were many other Taiwanese fantasy movies. However, to a western viewer such as me, the sights of kids playing with corpses and little child-zombies are a bit unnerving, to say nothing of once scene where one child attempts suicide. Similarly, the Chinese attitude towards religion was always a bit different from that of the west. It feels a tad irreverent to watch a Catholic priest stealing corpses, even if he is doing so for the sake of research and is shown in a generally sympathetic light (it’s his boss that provides the white-devil stereotype). Similarly, the movie seems to have no clue that sexually objectifying a nun might offend some Christians -- unlike European nunsploitation films, where the offensiveness is part of the fun -- and one has to wonder where the Catholic priest learned kung fu. Also, animal lovers should know that animals were indeed harmed during the making of the film.

Hello Dracula doesn’t provide the same mix of comedy, effective horror, strange fantasy and brutal stunts seen in the more popular Mr. Vampire, but it does provide an extensive degree of light-hearted cheer for a movie filled with violent death and hopping Chinese zombies. Chiu Chung-hing also directed Magic of Spell, the sequel to Child of Peach, as well as serving as action director for films like The Miracle Fighters (Yuen Woo-Ping, 1982). Certainly one of the driving factors in Chinese language fantasy/martial arts films, he’s rather underappreciated.

Hello Dracula doesn’t provide the same mix of comedy, effective horror, strange fantasy and brutal stunts seen in the more popular Mr. Vampire, but it does provide an extensive degree of light-hearted cheer for a movie filled with violent death and hopping Chinese zombies. Chiu Chung-hing also directed Magic of Spell, the sequel to Child of Peach, as well as serving as action director for films like The Miracle Fighters (Yuen Woo-Ping, 1982). Certainly one of the driving factors in Chinese language fantasy/martial arts films, he’s rather underappreciated.

The only other film I’ve been able to see in this series is 3-D Army (Chan Jun-Leung, 1989) which isn’t really an official entry. It’s a pity that these movies don’t even blip on the radar in the West. When watching a movie like Hello Dracula or Thrilling Sword, it isn’t fair to expect anything. These are, after all, movies made for children on the other side of the world in the primitive 80’s. Like most of the others I’ve reviewed, I would probably watch it with my own kids, if I had any. But with somebody else’s? No. Hell, no.

And no, the title doesn't make any more sense after having watched the movie.

The first in probably the longest running series of fantasy films during Taiwan’s infatuation with the genre during the eighties, Hello Dracula (aka 幽幻道士, Son of Chinese Vampire and Corpse Boy) receives very little attention here in the west, even among cult movie aficionados. It’s generally known only to die-hard kung fu movie fans, and even then, it isn’t widely discussed online, possibly because of the limited availability of both the original film and its sequels. (Granted, I probably just jinxed it and all six movies will end up on edonkey tomorrow morning, and yes, there are six) Of the many jiang-shi (or gyonshi/kyonsi) movies that came in the wake of Mr. Vampire (Ricky Lau, 1985) this is my favorite.

The first in probably the longest running series of fantasy films during Taiwan’s infatuation with the genre during the eighties, Hello Dracula (aka 幽幻道士, Son of Chinese Vampire and Corpse Boy) receives very little attention here in the west, even among cult movie aficionados. It’s generally known only to die-hard kung fu movie fans, and even then, it isn’t widely discussed online, possibly because of the limited availability of both the original film and its sequels. (Granted, I probably just jinxed it and all six movies will end up on edonkey tomorrow morning, and yes, there are six) Of the many jiang-shi (or gyonshi/kyonsi) movies that came in the wake of Mr. Vampire (Ricky Lau, 1985) this is my favorite.

For those not familiar with the “Chinese vampire/zombie” myth, it was once believed that in order for a human spirit to attain peace after death, their corporeal self should be buried in a pleasant place near their hometown. Taoists were charged with transporting corpses to their home towns, where they would be interred, and the myth of reanimated corpses that would hop along behind the magically endowed Taoist was born from this practice. There’s plenty of speculation as to why they’re so often depicted in Manchu style dress and the reasons why they detect people by smelling/feeling their breath, but that’s all rather academic. Look it up on Wikipedia.

For those not familiar with the “Chinese vampire/zombie” myth, it was once believed that in order for a human spirit to attain peace after death, their corporeal self should be buried in a pleasant place near their hometown. Taoists were charged with transporting corpses to their home towns, where they would be interred, and the myth of reanimated corpses that would hop along behind the magically endowed Taoist was born from this practice. There’s plenty of speculation as to why they’re so often depicted in Manchu style dress and the reasons why they detect people by smelling/feeling their breath, but that’s all rather academic. Look it up on Wikipedia.Set in what one assumes is the early twentieth century, Hello Dracula begins with a travelling Taoist transporting reanimated corpses through a dark forest and is accosted by a tiny hopping corpse boy. As the Taoist is getting beaten up by the little corpse boy, another Taoist, Grandpa King, is travelling through the same forest with his granddaughter, Ten-ten, his four other young apprentices/assistants, and the corpse of their former master in tow. Grandpa tells his charges that they should keep out of the forest, because the reanimated corpse of a child haunts it. No sooner does he inform them of the child than the other Taoist and the kid-zombie come crashing into his wagon, causing the corpse of Ten-ten’s former master to reanimate. The still living humans basically run away, happy to escape with their lives.

Back in town, the locals are upset by the idea that zombies haunt the surrounding forests, and the military governor of the town, whose elder brother recently died, demands that Grandpa King keep the reanimated corpses under control. Unfortunately, his chubby assistant, Shih Kua Pih, is a bit of a bumbling doof, and causes various problems with his clumsiness. Further complicating the situation is a group of foreigners who want the corpse for some sort of experiment. The poorly translated embedded subtitles don’t make it clear if said experiment is mystical or scientific in nature, as one of the corpse thieves is at least dressed as a Catholic priest, and his female companion a nun. Neither of them acts their respective parts, what with stealing corpses and doing sexy stripteases to distract the patrolling militia men.

Back in town, the locals are upset by the idea that zombies haunt the surrounding forests, and the military governor of the town, whose elder brother recently died, demands that Grandpa King keep the reanimated corpses under control. Unfortunately, his chubby assistant, Shih Kua Pih, is a bit of a bumbling doof, and causes various problems with his clumsiness. Further complicating the situation is a group of foreigners who want the corpse for some sort of experiment. The poorly translated embedded subtitles don’t make it clear if said experiment is mystical or scientific in nature, as one of the corpse thieves is at least dressed as a Catholic priest, and his female companion a nun. Neither of them acts their respective parts, what with stealing corpses and doing sexy stripteases to distract the patrolling militia men. The movie rambles between set-pieces. Ten-ten controls the corpses with a cute song-and-dance routine; the kid-zombie plays baseball with himself; there’s a comedy vignette with the male Taoist apprentices fighting over Ten-ten’s approval. It all boils down to a climax in which Ten-ten is captured by her former master’s zombie and the corpses all get lose and run wild over the town. Mayhem ensues and the audience is served a great display of kids doing acrobatics, ritual Taoist magic and kung fu.

The movie rambles between set-pieces. Ten-ten controls the corpses with a cute song-and-dance routine; the kid-zombie plays baseball with himself; there’s a comedy vignette with the male Taoist apprentices fighting over Ten-ten’s approval. It all boils down to a climax in which Ten-ten is captured by her former master’s zombie and the corpses all get lose and run wild over the town. Mayhem ensues and the audience is served a great display of kids doing acrobatics, ritual Taoist magic and kung fu.Liu Chih-Yu became a huge star in her role as Ten-ten, and director Chiu Ching-hung clearly chose to showcase her. As far as child stars go, she’s quite tolerable. Her male counterpart, the bumbling chubby kid Shih Kua Pih, is played by Liu Chih-han. He looks a bit older than the other kids and does pretty well with the comedy and the limited action scenes. Gam Tiu as Grandpa King pales in comparison to Lam Ching-Ying, but that comparison isn’t fair. He was a veteran Taiwanese actor and it shows in his performance. Boon Saam as the fat militia captain is quite funny.

Hello Dracula was definitely intended as a children’s film, as were many other Taiwanese fantasy movies. However, to a western viewer such as me, the sights of kids playing with corpses and little child-zombies are a bit unnerving, to say nothing of once scene where one child attempts suicide. Similarly, the Chinese attitude towards religion was always a bit different from that of the west. It feels a tad irreverent to watch a Catholic priest stealing corpses, even if he is doing so for the sake of research and is shown in a generally sympathetic light (it’s his boss that provides the white-devil stereotype). Similarly, the movie seems to have no clue that sexually objectifying a nun might offend some Christians -- unlike European nunsploitation films, where the offensiveness is part of the fun -- and one has to wonder where the Catholic priest learned kung fu. Also, animal lovers should know that animals were indeed harmed during the making of the film.

Hello Dracula was definitely intended as a children’s film, as were many other Taiwanese fantasy movies. However, to a western viewer such as me, the sights of kids playing with corpses and little child-zombies are a bit unnerving, to say nothing of once scene where one child attempts suicide. Similarly, the Chinese attitude towards religion was always a bit different from that of the west. It feels a tad irreverent to watch a Catholic priest stealing corpses, even if he is doing so for the sake of research and is shown in a generally sympathetic light (it’s his boss that provides the white-devil stereotype). Similarly, the movie seems to have no clue that sexually objectifying a nun might offend some Christians -- unlike European nunsploitation films, where the offensiveness is part of the fun -- and one has to wonder where the Catholic priest learned kung fu. Also, animal lovers should know that animals were indeed harmed during the making of the film. Hello Dracula doesn’t provide the same mix of comedy, effective horror, strange fantasy and brutal stunts seen in the more popular Mr. Vampire, but it does provide an extensive degree of light-hearted cheer for a movie filled with violent death and hopping Chinese zombies. Chiu Chung-hing also directed Magic of Spell, the sequel to Child of Peach, as well as serving as action director for films like The Miracle Fighters (Yuen Woo-Ping, 1982). Certainly one of the driving factors in Chinese language fantasy/martial arts films, he’s rather underappreciated.

Hello Dracula doesn’t provide the same mix of comedy, effective horror, strange fantasy and brutal stunts seen in the more popular Mr. Vampire, but it does provide an extensive degree of light-hearted cheer for a movie filled with violent death and hopping Chinese zombies. Chiu Chung-hing also directed Magic of Spell, the sequel to Child of Peach, as well as serving as action director for films like The Miracle Fighters (Yuen Woo-Ping, 1982). Certainly one of the driving factors in Chinese language fantasy/martial arts films, he’s rather underappreciated.The only other film I’ve been able to see in this series is 3-D Army (Chan Jun-Leung, 1989) which isn’t really an official entry. It’s a pity that these movies don’t even blip on the radar in the West. When watching a movie like Hello Dracula or Thrilling Sword, it isn’t fair to expect anything. These are, after all, movies made for children on the other side of the world in the primitive 80’s. Like most of the others I’ve reviewed, I would probably watch it with my own kids, if I had any. But with somebody else’s? No. Hell, no.

And no, the title doesn't make any more sense after having watched the movie.

12/20/09

Bald is the new lame

Let it not be said of me that I am outright opposed to remakes. I happened to like Werner Herzog's Bad Liutenant: Port of Call New Orleans, even if it basically spoofed the more important theme's from Ferrerra's film (which is admittedly superior). I'm actually looking forward to David Gordon Green's take on Suspiria. Really, I'm quite open to the whole idea of a remake so long as it doesn't suck.

That said, Louis Leterrier's new Clash of the Titans looks pretty dire.

It's difficult to even explain how obnoxious these new fantasy films are becoming without sounding like a film-Luddite or some sort of shrill Harryhausen fanboy. I'm not against the idea of remaking the 1981 Desmond Davis film in a more serious/not campy way. It would have helped if they'd actually, I don't know, treated it seriously. They only took the myth of Perseus seriously in the sense that superheroes and video games can be taken seriously. It's serious because it has seriously cool digital effects! Lots of people have used digital effects to spectacular ends, but looking the trailer for this just irks me. I don't want to see what Medusa would look like if she were designed to appeal to people who spend most of their free time playing God of War. And whatever happened to a palette of more than five colors?

It really does look like it could be based on a video game. You could splice most of that trailer in with the trailer for the upcoming Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time and probably nobody would notice. What's with all the bald, buff guys lately? And why do they all seem to fly through the air to stab at things?

I say this all provisionally, but the trailer doesn't inspire hope. Which is the point of these posts, wherein I try to figure out why I'm having a positive or negative reaction to something I haven't actually seen.

From the trailer, Clash of the Titans feels all too familar, and not because it's a remake. It's more because it looks like a retread of everything from Troy to 300. The market for movies involving myth and swordfighting and ancient warriors has reached full saturation, and the adaptations I was looking forward to (Conan and Solomon Kane) haven't even made it into theaters yet. I love movies about manly dudes hitting each other with sharp stuff, but they've all started to resemble each other, and I need a break from the overdesigned cgi set pieces, yelling, and "inspiring" speeches. If, in the upcoming adaptation, Conan doesn't say more than three full sentences, I'll be immensely happy.

That said, Louis Leterrier's new Clash of the Titans looks pretty dire.

It's difficult to even explain how obnoxious these new fantasy films are becoming without sounding like a film-Luddite or some sort of shrill Harryhausen fanboy. I'm not against the idea of remaking the 1981 Desmond Davis film in a more serious/not campy way. It would have helped if they'd actually, I don't know, treated it seriously. They only took the myth of Perseus seriously in the sense that superheroes and video games can be taken seriously. It's serious because it has seriously cool digital effects! Lots of people have used digital effects to spectacular ends, but looking the trailer for this just irks me. I don't want to see what Medusa would look like if she were designed to appeal to people who spend most of their free time playing God of War. And whatever happened to a palette of more than five colors?

It really does look like it could be based on a video game. You could splice most of that trailer in with the trailer for the upcoming Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time and probably nobody would notice. What's with all the bald, buff guys lately? And why do they all seem to fly through the air to stab at things?

I say this all provisionally, but the trailer doesn't inspire hope. Which is the point of these posts, wherein I try to figure out why I'm having a positive or negative reaction to something I haven't actually seen.

From the trailer, Clash of the Titans feels all too familar, and not because it's a remake. It's more because it looks like a retread of everything from Troy to 300. The market for movies involving myth and swordfighting and ancient warriors has reached full saturation, and the adaptations I was looking forward to (Conan and Solomon Kane) haven't even made it into theaters yet. I love movies about manly dudes hitting each other with sharp stuff, but they've all started to resemble each other, and I need a break from the overdesigned cgi set pieces, yelling, and "inspiring" speeches. If, in the upcoming adaptation, Conan doesn't say more than three full sentences, I'll be immensely happy.

12/12/09

I Dreamed a Dream of a World without Stupid Terminology Pertaining to Video Games

There's a NeoGAF discussion thread (that I found via the Hardcore Gaming 101 forum) wherein a bunch of gamers prattle on in pretend-intellectual speak about the words gamers use to define themselves and each other. I used to edit student essays for a college freshmen rhetoric class, so the tone of this discussion became terribly familiar less than half-way into the original post. But there's something admirable in much of what they say, even if some of the forum-goers aren't as capable of expressing it as others.

It does beg the question of what sort of "gamer" I might call myself. I hate the arbitrary term "hardcore," for all sorts of reasons, the least of which is that it doesn't denote anything concrete. The "esoteric gamer," the terminology proffered by the original poster in that thread, is even worse. Games are already esoteric to those who don't play them, and certain genres of games are obtuse to gamers who don't like them. The word casual now refers to people who play very simple games or buy non-game console software, like Wii Fit. I used to think of "casual" as a reference to people who play lots of Madden NFL 2Kwhatev, Halo, or some other simplified genre excursion. Those people are now referred to as "hardcore" by much of the gaming press, which I suppose is now comprised of little more than Game Informer, 1up, Kotaku and a billion amateur bloggers and forumites and youtube users.

But I also have to admit that I don't call myself a "gamer." Video games aren't my foremost hobby; I spend more time reading and watching movies than I do playing games. But even if video games took up more of my time (and I have been playing them more often, of late) I wouldn't want to personally identify myself with them. I wouldn't want to attach to my identity the title of "gamer." I've seen users on various forums and websites wondering why social networking sites have sections for favorite movies and books, but not video games. I never wondered that.

The matter of self-identification could easily solve itself. You're a "gamer" if you identify yourself as one. But that puts me in an untenable position, as I don't want to ascribe myself that kind of nomenclature, but I probably play more games than most non-nerdy people and know more about game history than the average Xbox Live loudmouth. The games that interest me are usually RPGs. I like dungeon crawlers and silly JRPGs with overly flashy graphics. I love Japanese developer Falcom, whom I make reference (and jokes) to pretty regularly on this blog. I'm also interested in arcade beat-em-ups, Koei/Omega Force games based on Chinese and Japanese history, and games from China and South Korea. I'm starting to think I'll give anything done by Vanillaware a shot.

My tastes are weird, and the games that I like are easily identified as games. I'm a firm opponent of the idea that games are art. (Not that they can't be, but that they aren't, generally) Am I a self-loathing gamer?

I think I've taken shots at Jeremy Parish, Christian Nutt, and Tim Rogers at some point or other on this blog. But really, I think that what they want out of games is more or less similar to what I want. I'll never agree with some of what Rogers puts on actionbutton.net, but I'm fairly (i.e. completely) certain he knows more about game design and the industry than I do.** I'll never agree with Nutt or Parish on some issues either, but the more I read of what they have to say, the less I think we're so different in what we like about video games. Yes, we all want a game that controls well and has fun/workable gameplay mechanics. But I think we're looking for some sort of human warmth as well. For me, that's Falcom's appeal, same for Troika -- even Blizzard at one point. I don't need a brilliant story out of Ys 7 or Temple of Elemental Evil. And I won't get them either. But those games feel as though they were made by people. People I might like.

There's probably a lot of people who feel that way about Valve, or the long defunct Looking Glass, or Treasure. Or at least, something like it.

Video games are made by people who have idiosyncrasies and personalities. I like seeing the evidence of this. Whatever title the game journalists, forum goers and other pedants and didacts would like to assign to this, I'll be happy to take it.

**Please Note: Rogers' site's design makes my eyes shout their safe word. If your eyes don't have a safe word, you should probably sit down and devise one before entering actionbutton.net.

It does beg the question of what sort of "gamer" I might call myself. I hate the arbitrary term "hardcore," for all sorts of reasons, the least of which is that it doesn't denote anything concrete. The "esoteric gamer," the terminology proffered by the original poster in that thread, is even worse. Games are already esoteric to those who don't play them, and certain genres of games are obtuse to gamers who don't like them. The word casual now refers to people who play very simple games or buy non-game console software, like Wii Fit. I used to think of "casual" as a reference to people who play lots of Madden NFL 2Kwhatev, Halo, or some other simplified genre excursion. Those people are now referred to as "hardcore" by much of the gaming press, which I suppose is now comprised of little more than Game Informer, 1up, Kotaku and a billion amateur bloggers and forumites and youtube users.

But I also have to admit that I don't call myself a "gamer." Video games aren't my foremost hobby; I spend more time reading and watching movies than I do playing games. But even if video games took up more of my time (and I have been playing them more often, of late) I wouldn't want to personally identify myself with them. I wouldn't want to attach to my identity the title of "gamer." I've seen users on various forums and websites wondering why social networking sites have sections for favorite movies and books, but not video games. I never wondered that.

The matter of self-identification could easily solve itself. You're a "gamer" if you identify yourself as one. But that puts me in an untenable position, as I don't want to ascribe myself that kind of nomenclature, but I probably play more games than most non-nerdy people and know more about game history than the average Xbox Live loudmouth. The games that interest me are usually RPGs. I like dungeon crawlers and silly JRPGs with overly flashy graphics. I love Japanese developer Falcom, whom I make reference (and jokes) to pretty regularly on this blog. I'm also interested in arcade beat-em-ups, Koei/Omega Force games based on Chinese and Japanese history, and games from China and South Korea. I'm starting to think I'll give anything done by Vanillaware a shot.

My tastes are weird, and the games that I like are easily identified as games. I'm a firm opponent of the idea that games are art. (Not that they can't be, but that they aren't, generally) Am I a self-loathing gamer?

I think I've taken shots at Jeremy Parish, Christian Nutt, and Tim Rogers at some point or other on this blog. But really, I think that what they want out of games is more or less similar to what I want. I'll never agree with some of what Rogers puts on actionbutton.net, but I'm fairly (i.e. completely) certain he knows more about game design and the industry than I do.** I'll never agree with Nutt or Parish on some issues either, but the more I read of what they have to say, the less I think we're so different in what we like about video games. Yes, we all want a game that controls well and has fun/workable gameplay mechanics. But I think we're looking for some sort of human warmth as well. For me, that's Falcom's appeal, same for Troika -- even Blizzard at one point. I don't need a brilliant story out of Ys 7 or Temple of Elemental Evil. And I won't get them either. But those games feel as though they were made by people. People I might like.

There's probably a lot of people who feel that way about Valve, or the long defunct Looking Glass, or Treasure. Or at least, something like it.

Video games are made by people who have idiosyncrasies and personalities. I like seeing the evidence of this. Whatever title the game journalists, forum goers and other pedants and didacts would like to assign to this, I'll be happy to take it.

**Please Note: Rogers' site's design makes my eyes shout their safe word. If your eyes don't have a safe word, you should probably sit down and devise one before entering actionbutton.net.

12/9/09

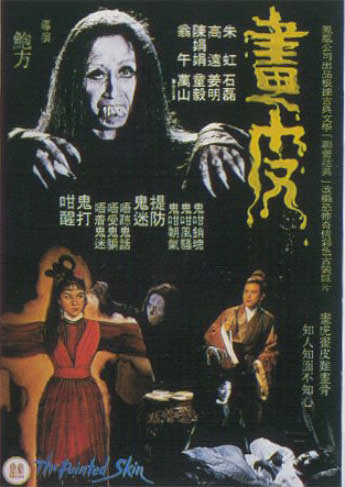

Painted Skin (Bao Fang, 1966)

Mainland Chinese cinema of the mid-1960 has all the spontaneity and human warmth of an algebraic equation, which is interesting when contrasted against the left-wing studios in Hong Kong. Although they’re known for having produced “serious” films -- literary adaptations, like Zhu Shilin’s 1961 adaptation of Cao Yu’s “Thunderstorm” -- the progressive studios also made genre films like Feng Huang’s tremendously expensive historical epic, The Golden Eagle (Chen Jingbo, 1964) or Great Wall’s wuxia classic The Jade Bow (Zhang XinYan, 1966). Painted Skin, a film from Feng Huang contract director Bao Fang, is itself a literary adaptation, but fits well with the previously mentioned films as a “soft film,” designed to entertain rather than instruct their audience.

The film frames the narrative as a story being told to Pu Songling. Pu authored the story collection, “Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio,” in the late seventeenth/early eighteenth century. Popular myth tells that Pu collected his stories from local passers-by and composed his collection out of their stories. There’s not much evidence to support this theory, but the film runs with it. It’s quaint and charming in equal measures.

Scholar Wong Chu Wen is an unsuccessful scholar studying to take the governmental exams in order to gain employment in lucrative administrative position. His brother advises him to forget about auspicious dates and omens and rely on his considerable knowledge of literature and history when he takes his exam -- a gentle way of saying “just study hard, you git.” All that goes out the window when a travelling Taoist tells him that success is in his future, and that to activate his good fortune, he should pray at an abandoned temple on his family’s property. Excited by this foretelling, Wong goes to the temple late at night, only to find a young lady. She tells him that she’s running away from an arranged marriage, set up by her cruel step mother, and that her father is a minister in charge of the examinations at the capital. Seeing this as an opportunity, Wong invites the girl, Mei-niang, to hide away in his study, and that he’ll take her with him to the capital.

He doesn’t tell his wife, or his mother, or his servants about Mei-niang and locks himself in his studio to “study,” spending days and nights there. He doesn’t tell Mei-niang about his wife. I trust the reader can see where this is headed.

Eventually, Mei-niang finds out about Hsia-ling, the scholar’s wife, and is incensed. She tells Wong that she thought that he would marry her once he earned a governmental position, but that now she has no chance at a socially advantageous marriage. Wong ruined her by ruining her.

To rectify the situation, Mei-niang decides that Wong should kill his wife, a task that Wong fails at completing. It is then that strange things start to happen at night, and an awful secret about Mei-niang comes to light.

Painted Skin works because outside of the opening scene, it avoids pedantry. “I know that you are using your tales of ghosts and demons to express your sense of justice,” is about as far in that direction as the opening with Pu Songling actually goes. The rest of the story slowly builds to the horrific reveal. Mei-niang is a ghostly spirit, and beautiful female ghosts and fox demons are well known as the natural predators of hapless scholars in medieval China. And while the film doesn’t follow every detail of the story, likely to avoid the disgusting sequence involving lots of (I’m not kidding) phlegm, it’s probably the most faithful cinematic recreation of one of the “Strange Tales...,” excusing its lapses in textual fidelity by framing it as the tall tale that eventually inspired the story that made it into Pu’s collection. Hence, Wong is really a complete dick, and it’s hard to feel bad for him. That’s about normal for many of the male protagonists in the “Strange Tales...”

As for how it is as a movie, Painted Skin exudes that classic glamour that makes golden age Hong Kong cinema so enjoyable. The way that the film fades out whenever something naughty is about to happen is utterly charming. It feels theatrical at times, with its long shots and careful staging, but isn’t un-cinematic. The moments leading up to the ghostly terror actually muster some real tension, and my only wish was that the film spent an extra ten minutes with its depiction of the supernatural. The simple make up effects and eerie atmosphere make for some effective moments of horror. But up until these moments, one unfamiliar with its source material might assume Painted Skin a very bleak period drama, rather than a horror-fantasy. And it’s a very good, if rather dated period drama up until that point.

An always thought provoking comparison is to look at stories that are frequently adapted as cinema and compare the treatment they receive in each decade or era. Comparing this restrained, conservative film with King Hu’s somewhat uncharacteristic adaptation from 1993 or Gordon Chan’s overproduced wuxia-grotesque from last year will probably give a very wrong impression of Hong Kong cinema’s progress. But it’s a fun time, and will provide an excuse to watch this quaint, sweet little ghost story.

12/3/09

2009 Sucks

Earlier this year, legendary director/cinematographer Jack Cardiff, a man whose career spanned the majority of cinema history, died. David Carradine's death later overshadowed those of legendary Hong Kong cinema villain Shek Kin and Shaw Brothers stalwart Ho Meng-hua, director of classic films like Suzanna and The Lady Hermit. Then Lou Albano; then Shing Fui-On. Michael Jackson. Does anybody need to say more?

Another three: Paul Naschy, Chen Hunglieh and Ding Shanxi. I liked these guys, or at least some of the movies they made/appeared in.

2009 is almost over. It needs to hurry up and end.

Another three: Paul Naschy, Chen Hunglieh and Ding Shanxi. I liked these guys, or at least some of the movies they made/appeared in.

2009 is almost over. It needs to hurry up and end.

11/29/09

David Gaider Is Made of Cheese -- A Review of Dragon Age: The Stolen Throne

I’d like to share with you the following statement by youtube user hyrulehistorian, posted on Bioware’s youtube page for their new game, Dragon Age: Origins.

“this is legit, im reading the prequel novel right now, and im getting the feeling in my gut that we are seeing the birth of what will become one of the all time great fantasy universes.”Do I seem hung up on what other people like? If I am, it’s because of statements like that.

As a preface to my review of David Gaider’s Dragon Age: The Stolen Throne, I must say something of my stance on franchise novels. Franchise novels allow the terminally uncreative the pleasure of saying that they read without actually requiring much beyond functional literacy. Rather than asking the reader to stick with the author as he or she tells a story, the tie-in novel asks for the player to read up on a familiar setting, characters, or events out of brand loyalty, or to satisfy the inherently nerdy obsession with (entirely made up) minutia and trivia. The plots cannot interfere with each other, or an excuse must be made for why person x is still around when person x previously left/died/inter-dimensionally relocated in one of the previous novels/games/comic books. These products exist solely to market the video games on which they’re based, with the hope that the video games will hook people into buying the novels to learn more about the setting, and the made up lore, or the political/religious/historical conflicts that might be only obliquely mentioned in the game.

Here’s a quote from Game Informer’s (Issue 175, pg 151) review of Mass Effect, which I think illustrates the mindset of somebody who reads tie-in novels, and likely nothing but tie-in novels:

“[Mass Effect] is an amazing work of fiction, a visual work of art, and a property that is so fully realized and so rich in its backstory that its content could fill countless games, books, and movies. This is the next big franchise for science fiction junkies to latch onto, and a huge step forward for video games.”

What does this tell us, besides that editor Andrew Reiner is a giant rube? Think about the idea that the “backstory” could “fill countless games, books, and movies.” That’s pretty much the greatest virtue that anything could have for the sort of audience that reads Game Informer. Despite all of the breathless superlatives Reiner ascribes to Mass Effect as fiction, the one element that he actually delineates is the milieu and the world-building that accompanies it, because that’s all that matters to him. It’s something for the people he thinks are “science fiction junkies” to escape in and over which they can argue, until the next novel or game comes out and provides a conclusive answer. Essentially, it’s there to answer all the questions, raise just enough new ones to keep its audience interested in the next product, and prevent them from thinking too hard.

Dragon Age: The Stolen Throne fits well in this line of thinking.

It opens with Maric being chased down by the underlings of traitorous banns (apparently, the word bann substitutes for the word baron in David Gaider’s D&D campaign) who just killed his mother, the rightful queen of Ferelden. Maric escapes capture only to find himself in the company of Loghain, whose father leads a large band of outlaws. The outlaws were once good citizens, until the unfair taxes of the newly appointed King Meghren of Orlais forced them to willingly break the law. Maric doesn’t tell them that he is the prince and that his mother, the rebel queen, has died, or that Meghren’s troops will be looking for him. Consequently, the camp of outlaws is raided, and Loghain’s father demands his son help restore Maric to the rebel army. Of course, Loghain’s father dies, giving Loghain a reason to be emo for a while, and Maric a chance to win him over as a friend who will do all of Maric’s dirty work.

It opens with Maric being chased down by the underlings of traitorous banns (apparently, the word bann substitutes for the word baron in David Gaider’s D&D campaign) who just killed his mother, the rightful queen of Ferelden. Maric escapes capture only to find himself in the company of Loghain, whose father leads a large band of outlaws. The outlaws were once good citizens, until the unfair taxes of the newly appointed King Meghren of Orlais forced them to willingly break the law. Maric doesn’t tell them that he is the prince and that his mother, the rebel queen, has died, or that Meghren’s troops will be looking for him. Consequently, the camp of outlaws is raided, and Loghain’s father demands his son help restore Maric to the rebel army. Of course, Loghain’s father dies, giving Loghain a reason to be emo for a while, and Maric a chance to win him over as a friend who will do all of Maric’s dirty work.Eventually, Loghain manages to put Maric back into contact with the army. Loghain falls in love with Rowan, Maric’s betrothed, while Maric falls in love with an elf named Katriel as they campaign against the Orlaisian usurper. Then the army suffers a major loss, and Maric, Loghain, Katriel and Rowan have to travel through the Deep Roads (i.e. Mines of Moira) where they encounter giant spiders, darkspawn (orcs), and Dwarves who agree to help Maric regain the thrown. But even after making it safely back to the surface, Maric must face treachery and the difficult reality of a king’s duty.

Does it all sound like generic fantasy plot #5? It is generic fantasy plot #5, and Gaider doesn’t do much to make it worth reading. The pacing in the first half janks about due to it being primarily about Maric’s military campaign, and settles into a rote dungeon crawling sequence for much of the final act. But one might forgive the plotting were it not for the characterization, which reeks of cliché. Maric is blonde, handsome, and noble; he loves his subjects and cares for people to a fault. He’s naïve. He’s unsure of himself and incompetent as a strategist. Yet all the women love him, and he inspires hope among every warrior he meets with what Gaider calls “infectious charm,” and I call grating attempts at sophomoric wit, always ready with some flaccid quip when the tone gets too serious. He’s the self-portrait a lot of nerds paint when they’re being dishonest. He’s destined to not suck.

Loghain is an equally lazy stock character, an angsty, brooding fellow with “piercing blue eyes.” Rowan is too. She’s an Amazonian lady-warrior who wants Marric to see her as a woman, not just a warrior. Meghran is a debauched, violent pussy who has no redeeming qualities or even a personality. Severan, his right hand man and sorcerer, is an equally violent, though much more effective pussy, and has no redeeming qualities or even a personality. Dwarves build tunnels and hit things with warhammers. Elves shoot bows, and… uh, are pretty, I guess. Ugh.

Even Gaider’s writing is leaden and expository, frequently juvenile in the worst places and in the worst ways. Among the more embarrassing aspects of the prose is Gaider’s commitment to adverbs, particularly in certain paragraphs where every sentence contains at least one. For example:

Even Gaider’s writing is leaden and expository, frequently juvenile in the worst places and in the worst ways. Among the more embarrassing aspects of the prose is Gaider’s commitment to adverbs, particularly in certain paragraphs where every sentence contains at least one. For example:“Maric dug into his stew ravenously. Katriel picked at hers gingerly, sipping on some of the broth. The dwarf all but gulped his down greedily, finishing it long before the others were even half done, and then belching loudly. He wiped his beard with the back of his hand.That whole passage is just infuriating. It’s like filling out a list: this person does this, this way. This person does this, this way. This person does this, this way, then does this, this way. That’s not to even mention the context of this scene, in which Maric and Katriel have just walked for miles, injured and without much food or water, and Katriel is picking at her food rather than just eating it. It’s terribly lazy writing, acceptable in a first draft but damning in published work from somebody who claims writing as his profession.

‘Not as Hungry as you thought?’ he asked, watching their progress.

‘No it’s fine,’ Maric quickly commented…”

Another gem:

“Maric stared at her in disbelief. He wasn’t quite sure she could have said anything else that would have been less surprising. Well perhaps a confession that she was actually made of cheese.”Frankly, I’d be less than surprised were the admission Mr. Gaider’s.

In defense of Dragon Age: The Stolen Throne, there are moments when it isn’t horrible to read. I liked when Maric confronted the banns who killed his mother. I liked that David Gaider at least tried to develop a theme of the unpleasant, even morally reprehensible things that must be done in order to effectively govern, and the guilt that accompanies them. The battle descriptions plod, but Gaider, in his mercy, spares his readers a similar treatment of sex (and rape). I appreciate that the obligatory dragon scene doesn’t involve telepathic communication.

But these moments are few, and they don’t mitigate flawed nature of the narrative, the writing, and the prose, even the setting. The world feels Tolkeinesque -- Dwarves, elves, etc. -- with some French and some fabricated titles. Knights are called chevaliers, for reasons I don’t really care to ponder, although I suppose that Orlais could be some sort of caricatured French empire. Various characters of high rank have titles like arl (earl), bann (baron?), and Teyrn (I’m flummoxed). Worse, Gaider doesn’t seem familiar enough with Medieval custom and manner to know that “your highness,” “your grace,” “your majesty,” and “my lord” all relate specifically to people of different ranks. The portrayal of magic is right out of a video game. All that’s missing is “Magic Missile!” or maybe “Blizzara!” Is all this nit-picky? I don’t care. It annoyed me.

Dragon Age: The Stolen Throne also speaks the veracity of that old truism, “write what you know.” Let me amend that: If you don’t know anything, don’t write. Or, if you don’t know anything, write for a video game. Or a video game franchise novel.

David Gaider is the lead writer for Bioware’s video game, Dragon Age: Origins, of which I’ve heard good things. I disliked, immensely, the marketing for that game, and I dislike this novel, which is part of said marketing. There are those who excuse this kind of writing as being purely escapist, not worthy of any praise, but also not deserving of a thorough critique. To this, I say that there is a great deal of escapist fantasy that’s actually engaging, intelligent, and well written. Franchise novels, by and large, aren’t. They’re books designed for people who don’t read, to ensure that they won’t read as much as they watch movies, play video games, and buy enormous card collections and rule books.

It isn’t actually that much fun to rip something like Dragon Age: The Stolen Throne on the internet. But such novels developed a huge market, allowing kids and tasteless adults like hyrulehistorian the undue (mostly imagined) honor of being a “reader” -- the fun of feigning literacy on their youtube and facebook profiles. Consider this a referendum on all video game, card game, board game, and Star Wars/Star Trek/whatever novels. When I go to my local book store and there’s no longer a full three rows devoted to this crap, I’ll take this review down, and replace it with my assurances that David Gaider’s probably a swell Canadian fellow IRL.

Be sure to read my review of David Gaider's follow up to The Stolen Throne, Dragon Age: The Calling. It sucks too.

11/20/09

The 2009 Bad Sex in Fiction Award...

Just fucking give it to Nick Cave already.

The prize hasn't had such great material to work with since... well, Norman Mailer's last novel. Ok, that wasn't that long ago. So let's just say it hasn't had such great material since ever. I haven't read most of the books on the list. Now I want to.

The prize hasn't had such great material to work with since... well, Norman Mailer's last novel. Ok, that wasn't that long ago. So let's just say it hasn't had such great material since ever. I haven't read most of the books on the list. Now I want to.

11/17/09

Game Review -- Orcs and Elves

I don’t have a cell phone that can run cell phone games of any complexity, because I use my cell phone as a phone, not a low-end Gameboy. But games on cell phones are kind of a big deal now, as I was informed by a co-worker who showed off the various games he had on his iPhone -- Mega Man 2, NetHack, and a bunch of other piddly time wasters. It’s funny that yesteryear’s phone/game system, the Nokia N-Gage, failed as badly as it did, only to see cell gaming become massively popular on iPhones and Blackberries. It’s also sad, because the N-Gage was the only way to play Falcom’s Xanadu Next in English, legally.

But what surprises me is the idea that anybody would port a cell phone game to one a commercially viable console. There are a few examples, like Deep Labyrinth on the DS and Final Fantasy 4: The After Years for the Wii’s virtual console, but the concept still baffles me to the point that when I read a review and it simply states that game x is adapted from cell phone game franchise y (and it isn't a puzzle/popcap game) it's surprising.

Orcs and Elves is another cell phone game ported to the DS, and like Deep Labyrinth, it’s a first person dungeon crawler. The DS is already a popular system for RPGs, with both Japanese and western style games (and Japanese riffs on western style dungeon crawlers) readily available, so to stand out, a game either has to utilize the DS’ unique features (touch pad, dual screens) in an unusual way, or just be really, really good.

Orcs and Elves doesn’t stand out. But that doesn’t mean it’s a bad game. It simply means that the stylus/touch pad control doesn’t add anything and that it’s a merely decent game rather than an excellent one. Considering its origins, that’s as good as anybody should hope for. It looks much like a mid-nineties era PC game, and plays similarly with a simple, turn-based system (your enemies don’t move until you do). But it was developed by John Carmack, the man behind Doom, and the cell phone game, Doom RPG. It’s fitting.

In fact, the game can be compulsively playable. The level designs contain a few secrets each, although they don’t really feel like mazes -- they’re cake compared to the more obtuse dungeon crawlers released for DOS PCs. The game limits what you can do with your character, but it never loses its identity as a role playing game. Stats provide the basis for what your character can do, and there’s plenty of potions that will boost stats (for a limited number of turns), and upgrades for the sword, and other stuff that can be bought. The magic system comes from your talking wand, itself a character with more personality than the player’s never-seen avatar. The Wand shoots projectiles which deplete magic points, as do various items and spells activated by tracing a pattern on the touch screen, but not until after they’ve already been selected, making the stylus tracing little more than an interruptive formality.

So what other reason might one play Orcs and Elves? Nostalgia comes to mind most readily, and humor too. The graphics -- pixelized sprites against low resolution 3D environments -- remind me of Bethesda’s old PC games, as well as old fantasy themed PC shooters like Hexen. It seems like the limitations of its original platform dictated that the graphics look as they do, but it also seems that the developers intententionally evoke memories of those older fantasy-themed games. After all, they could have easily added more animation when porting to the DS. It’s nice to see some retro-PC style outside of an indie game, if only on the DS.

Also, the story is preposterous enough to be funny. Particularly as it is relayed through notes scattered about the labyrinth, which are written in first person but frequently include (cough)s and ***Wheeze*** as if the author actually took pains to write out his bodily failings while he died. It’s an old gag (Monty Python and the Holy Grail, among others) but the developers seem to think it’s so funny that it’s easy to laugh at in spite of itself.

I beat Orcs and Elves in just under eleven hours, because I was being thorough. Rushing through without bothering with secrets or monster hunting, it’s probably a nine hour game. I don’t know what it was at full price, but I bought mine used and was fairly satisfied with it. The problem: it’s a cell phone game, and that’s probably the best platform for it. The game is playable and fun in short spurts, but tedious when you’ve played it for a few hours, because it’s only meant to be played for as long as you sit on the bus. It’s both unexpected and strange to think that a game might actually work better on a cell phone, but that is absolutely the case with this one.

But what surprises me is the idea that anybody would port a cell phone game to one a commercially viable console. There are a few examples, like Deep Labyrinth on the DS and Final Fantasy 4: The After Years for the Wii’s virtual console, but the concept still baffles me to the point that when I read a review and it simply states that game x is adapted from cell phone game franchise y (and it isn't a puzzle/popcap game) it's surprising.

Orcs and Elves is another cell phone game ported to the DS, and like Deep Labyrinth, it’s a first person dungeon crawler. The DS is already a popular system for RPGs, with both Japanese and western style games (and Japanese riffs on western style dungeon crawlers) readily available, so to stand out, a game either has to utilize the DS’ unique features (touch pad, dual screens) in an unusual way, or just be really, really good.

Orcs and Elves doesn’t stand out. But that doesn’t mean it’s a bad game. It simply means that the stylus/touch pad control doesn’t add anything and that it’s a merely decent game rather than an excellent one. Considering its origins, that’s as good as anybody should hope for. It looks much like a mid-nineties era PC game, and plays similarly with a simple, turn-based system (your enemies don’t move until you do). But it was developed by John Carmack, the man behind Doom, and the cell phone game, Doom RPG. It’s fitting.

In fact, the game can be compulsively playable. The level designs contain a few secrets each, although they don’t really feel like mazes -- they’re cake compared to the more obtuse dungeon crawlers released for DOS PCs. The game limits what you can do with your character, but it never loses its identity as a role playing game. Stats provide the basis for what your character can do, and there’s plenty of potions that will boost stats (for a limited number of turns), and upgrades for the sword, and other stuff that can be bought. The magic system comes from your talking wand, itself a character with more personality than the player’s never-seen avatar. The Wand shoots projectiles which deplete magic points, as do various items and spells activated by tracing a pattern on the touch screen, but not until after they’ve already been selected, making the stylus tracing little more than an interruptive formality.

So what other reason might one play Orcs and Elves? Nostalgia comes to mind most readily, and humor too. The graphics -- pixelized sprites against low resolution 3D environments -- remind me of Bethesda’s old PC games, as well as old fantasy themed PC shooters like Hexen. It seems like the limitations of its original platform dictated that the graphics look as they do, but it also seems that the developers intententionally evoke memories of those older fantasy-themed games. After all, they could have easily added more animation when porting to the DS. It’s nice to see some retro-PC style outside of an indie game, if only on the DS.

Also, the story is preposterous enough to be funny. Particularly as it is relayed through notes scattered about the labyrinth, which are written in first person but frequently include (cough)s and ***Wheeze*** as if the author actually took pains to write out his bodily failings while he died. It’s an old gag (Monty Python and the Holy Grail, among others) but the developers seem to think it’s so funny that it’s easy to laugh at in spite of itself.

I beat Orcs and Elves in just under eleven hours, because I was being thorough. Rushing through without bothering with secrets or monster hunting, it’s probably a nine hour game. I don’t know what it was at full price, but I bought mine used and was fairly satisfied with it. The problem: it’s a cell phone game, and that’s probably the best platform for it. The game is playable and fun in short spurts, but tedious when you’ve played it for a few hours, because it’s only meant to be played for as long as you sit on the bus. It’s both unexpected and strange to think that a game might actually work better on a cell phone, but that is absolutely the case with this one.

11/12/09

Arhats in Fury (Wang Singlui, 1985)

In Sung dynasty Sichuan, the monks of a Buddhist temple debate whether they should help repel the invading Jin armies or withdraw entirely from earthly politics, preserving their monastery and their centuries old regulations. When Zhi Xing and his senior return from a journey of punishment for breaking the temple rules, they come across the Jin’s raping and pillaging a small local town. Zhi Xing finally uses his kung fu to defeat the Jins after they kill a small child. While Zhi Xing successfully expels the invaders with the help of the local militia, he also brings their attention to the monastery, where the monks must confront the Jins. The reaction of the abbot and senior monks is stoicism, while the Jins begin to kill them, attempting to provoke a reaction, until Zhi Xing finally responds. Repelling them again, the monks wish to further punish Zhi Xing for repeatedly breaking their rules regarding martial arts, but he is saved by a beautiful woman, one of the leaders of the local militia whom he met during the battle in the town.

The townspeople nurse Zhi Xing back to health, while the Jin armies besiege the Buddhist temple. Of course, this finally causes the monks to reconsider their position on self-defense.

Roughly the first fifteen minutes expound the inner workings of the monastery. The punishments, like the long journey from which Zhi Xing and his master return, are harsh, and potentially life-threatening. The senior monks manipulate the abbot and are more bound to the antiquated rules than he is. The abbot is impressed with the insight of a monk he sent into exile decades ago, but comes back unafraid to criticize the way the temple operates. All this happens before Zhi Xing appears on screen, and while the location shooting looks pretty nice and the temple’s drama interesting in itself, the viewer will probably want to know when the kung fu will start.

Arhats in Fury isn’t an odd movie by the standards of the brief spurt of mainland Chinese kung fu films designed to showcase Wushu made in the wake of Shaolin Temple (Zhang Xinyan, 1982). It has the requisite animosity towards Buddhism -- one of Mao’s many grinds was religion, for reasons that ought to be obvious from the plot description of any of these movies -- the authentic location shooting and the 1980’s mainland aesthetic. It is strange for a director like Wong Singlui, usually associated with Hong Kong and Taiwan film industries. The influence of Hong Kong’s new wave directors occasionally comes out in his direction, but the major influence clearly comes from the propaganda war/action films of China’s film industry. The location shooting is immaculate. The images of monkeys and birds, especially, are striking. It moves from being a straight kung fu picture of the Hong Kong/Taiwan tradition, to typical PRC propaganda, to a wildly aesthetic pictorial of Sichuan.

The aforementioned animals too, make for one of the stranger parts of the movie, as well as the most unpleasant. There is real footage of animal death. The actors kill birds graphically, in one scene. Zhi Xing, apparently, has king-of-the-Sichuan-province powers over the animals, and during one skirmish, calls them in to help fight the Jins. It's a sign of Chinese language cinema's growing pains that the film makers behind a kung fu movie lifted ideas wholesale from Alfred Hitchcock's The Birds just because they could. And the images of monkeys communing with the monks, looking as though they’re praying monks or Buddha idols are far more unusual than what would one would typically associate with the genre during the late seventies.

Probably the nicest thing to be said about Lau Jan-Ling in his role as Zhi Xing is that he’s a perfectly capable martial artist. As an actor, he either over-emotes or stares into the distance like he doesn’t know what else to do. The actress who plays his romantic interest, the leader of the people’s militia (another Maoist propaganda element) has a similar on/off style of acting. The actors playing the Jins are camp. The actors playing the corrupt monks have little to do besides look angry.

But all of that stuff doesn’t really matter once people start hitting each other in the face. Arhats in Fury is among the best of this strain of Chinese films. The athleticism of the performers provides enough gloriously choreographed mayhem, but the sheer number of people in certain scenes further adds to the spectacle. The weapon choreography also, is among the best that the mainland offered, exceeded only by The South Shaolin Master (Siu Lung, 1984). If any movie were ever buoyed by its action scenes, it’s this one. Casting most of the roles with wushu experts assures that the fight scenes will impress, and its unsurprising that the only times that the action scenes don’t work is either due to rough editing or unnecessary wire work.

Animal lovers and those sensitive about propaganda will probably not like Arhats in Fury. There is much to be said about its portrayal of Buddhist pacifism, whether it intentionally misrepresents or obfuscates the intentions of that religion’s tenants. The very concept is heavier than the film itself. Whenever you watch one of these films, you have to wonder how much of the screenplay was intended as a way to get past the very active censors, as opposed to what the film makers actually cared about producing. Given the director, I’d think that the real concern was with beautiful location shots and brutal, impeccably choreographed action. But with as much time as is spent with the monastery, I can’t say that for certain.

The townspeople nurse Zhi Xing back to health, while the Jin armies besiege the Buddhist temple. Of course, this finally causes the monks to reconsider their position on self-defense.

Roughly the first fifteen minutes expound the inner workings of the monastery. The punishments, like the long journey from which Zhi Xing and his master return, are harsh, and potentially life-threatening. The senior monks manipulate the abbot and are more bound to the antiquated rules than he is. The abbot is impressed with the insight of a monk he sent into exile decades ago, but comes back unafraid to criticize the way the temple operates. All this happens before Zhi Xing appears on screen, and while the location shooting looks pretty nice and the temple’s drama interesting in itself, the viewer will probably want to know when the kung fu will start.

Arhats in Fury isn’t an odd movie by the standards of the brief spurt of mainland Chinese kung fu films designed to showcase Wushu made in the wake of Shaolin Temple (Zhang Xinyan, 1982). It has the requisite animosity towards Buddhism -- one of Mao’s many grinds was religion, for reasons that ought to be obvious from the plot description of any of these movies -- the authentic location shooting and the 1980’s mainland aesthetic. It is strange for a director like Wong Singlui, usually associated with Hong Kong and Taiwan film industries. The influence of Hong Kong’s new wave directors occasionally comes out in his direction, but the major influence clearly comes from the propaganda war/action films of China’s film industry. The location shooting is immaculate. The images of monkeys and birds, especially, are striking. It moves from being a straight kung fu picture of the Hong Kong/Taiwan tradition, to typical PRC propaganda, to a wildly aesthetic pictorial of Sichuan.

The aforementioned animals too, make for one of the stranger parts of the movie, as well as the most unpleasant. There is real footage of animal death. The actors kill birds graphically, in one scene. Zhi Xing, apparently, has king-of-the-Sichuan-province powers over the animals, and during one skirmish, calls them in to help fight the Jins. It's a sign of Chinese language cinema's growing pains that the film makers behind a kung fu movie lifted ideas wholesale from Alfred Hitchcock's The Birds just because they could. And the images of monkeys communing with the monks, looking as though they’re praying monks or Buddha idols are far more unusual than what would one would typically associate with the genre during the late seventies.

Probably the nicest thing to be said about Lau Jan-Ling in his role as Zhi Xing is that he’s a perfectly capable martial artist. As an actor, he either over-emotes or stares into the distance like he doesn’t know what else to do. The actress who plays his romantic interest, the leader of the people’s militia (another Maoist propaganda element) has a similar on/off style of acting. The actors playing the Jins are camp. The actors playing the corrupt monks have little to do besides look angry.