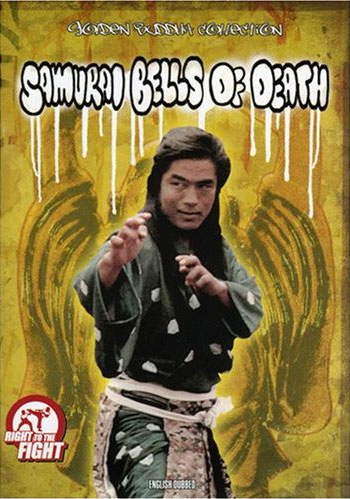

Here would be a great entry in the halls of legendarily terrible re-titles. Beauty Escort is also known as “Samurai Bells of Death,” the English title that appears on the English dubbed print, a reference to a weapon that appears in the movie called The Death Song Bells. One assumes that “Samurai” was added to the title so as not to be confused with Yueh Feng’s 1968 Shaw Brothers film, Bells of Death. It (Beauty Escort, not Bells of Death) is also based on the Gu Long novel Hu Hua Ling (护花铃), available in English translation under the title The Flower Guarding Bells. Perhaps a clue as to what sort of movie Beauty Escort is, the explanation of the title itself is convoluted enough to have been devised by Gu Long.

Here would be a great entry in the halls of legendarily terrible re-titles. Beauty Escort is also known as “Samurai Bells of Death,” the English title that appears on the English dubbed print, a reference to a weapon that appears in the movie called The Death Song Bells. One assumes that “Samurai” was added to the title so as not to be confused with Yueh Feng’s 1968 Shaw Brothers film, Bells of Death. It (Beauty Escort, not Bells of Death) is also based on the Gu Long novel Hu Hua Ling (护花铃), available in English translation under the title The Flower Guarding Bells. Perhaps a clue as to what sort of movie Beauty Escort is, the explanation of the title itself is convoluted enough to have been devised by Gu Long.Also, whoever came up with the English title was a liar. There are no samurai in Beauty Escort. It’s kind of like the Taiwanese Gu Long adaptation, The Lost Swordship, which has the alternate title “The Lost Samurai Sword,” in spite of there being no samurai or samurai swords in that film either. Unlike The Lost Swordship, however, Beauty Escort is unavailable in a widescreen, English language print. I watched the film on a Crash Cinema disc sourced from a terrible pan-and-scan VHS source, which is still better than the film being lost or prohibitively scarce.

The film starts with a duel between the Dragon and Phoenix clans, planned ten years prior. Dragon, leader of the Dragon Clan, has prepared to fight Phoenix, leader of the Phoenix Clan, but she died shortly before the duel was to take place. So a subordinate agrees to fight. Only she has less internal strength than Dragon, so, to insure a fair fight, he asks his subordinates to handicap him before the duel. Dragon’s daughter and her husband, Fei Ya, don’t really like this idea, but Nam Goong Ping agrees. Dragon and Phoenix Clan’s Yee Man Ching go to a secluded spot to duel, with Man Ching returning as the victor.

Already shocked by the outcome, the Dragon Clan receives an even greater surprise by Dragon’s will, which names Nam as his successor, rather than Fei Ya or his wife. The Dragon Clan hardly has time to fight amongst themselves, though, as bandits immediately arrive to steal their dead master’s coffin. Nam manages to apprehend the bandit as he runs away, only to find out that the bandits do not intend to steal any of the precious jewels from the coffin. They believe that the coffin hides a criminal in the martial world, a villainous seductress and master swordfighter by the name of “Cold Blooded Mistress” Mei Win Shu.

As it turns out, she’s hiding in a false bottom in the coffin, but she is not a villainess. She has been framed by various elements within the martial world who sought to force her into marriage, rape her, or otherwise subjugate her. After a duel, Dragon found out the truth, and hid her for eight years, his final wish that Nam would protect her and help to restore her reputation. In the mean time, Fei Ya and Dragon’s daughter have designs to take control of the Dragon Clan for themselves, while the shady business of how the Phoenix Clan won the duel has not been resolved and Nam’s wealthy, powerful family faces danger from growing forces who intend to seize their fortune.

So it is rather par the course for a Gu Long adaptation, convoluted and prone to barely explained coincidences. The dubbing is a problem, as it refers to some characters only by their nicknames – Dragon’s full name, Long Bushi, is never uttered – and others are not named at all, hence my referring to “Dragon’s Daughter.” And, like many of Gu Long’s stories, Beauty Escort is not really so much about the martial arts and clan rivalries, but about the romance between two of the protagonists, Nam and Mei Win Shu.

Unless the movie was also re-edited for its English dubbed version (a very real possibility), Beauty Escort devotes very little of its duration to the relationship between Nam and Wei, although even an inattentive viewer could tell where it’s headed once they meet. It’s not only unfortunate in that it ignores what was likely a central part of the novel, it lessens the opportunity for the sort of dialog that makes Gu Long fun to read or watch. Gu writes marvelous passive aggression, misdirection, and projection, all of which make for lively conflict and lively romance. Again, the dubbing captures none of this, assuming that it was ever there in the first place (also a very real possibility).

It’s hard, then, to give this movie a fair review, a problem endemic to kung fu and wuxia movies in general. Because of the broad perception that the appeal of this genre lies entirely in fight scenes, they were often dubbed without care. For reasons much more complicated, they were released on VHS in pan-and-scan, usually positioned to chop off embedded subtitles, the original prints often not well-preserved. So even visually, this film has been handicapped.

Which is a shame, since it was directed by alumni Shaw Brothers cinematographer Pao Shuh-Li, scripted by alumni Shaw Brothers screenwriter Katy Chin Shu Mei, and produced by legendary screen fighter Phillip Ko Fei. Stars Ling Yun and Nora Miao. Chan Wei Man plays the villain! It even looks like it had a bit more of a budget than a lot of other independent Hong Kong genre films. The fight scenes are acceptable, but it’s pretty clear that the movie is aiming for more than a highlight reel of kung fu sequences.

So, hey, if a nice, clean print shows up, maybe I can watch this movie again and give it a fair review. But the most seen, most available version of Beauty Escort is far from ideal, and with so many great films based on Gu Long novels available, it’s far from a must-see.