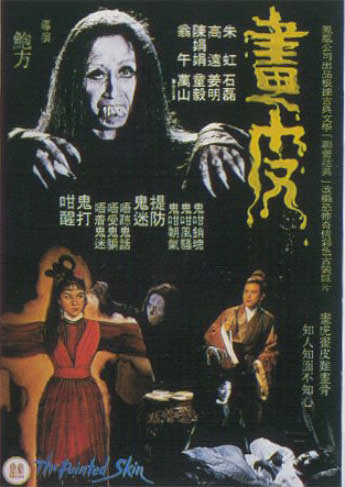

Mainland Chinese cinema of the mid-1960 has all the spontaneity and human warmth of an algebraic equation, which is interesting when contrasted against the left-wing studios in Hong Kong. Although they’re known for having produced “serious” films -- literary adaptations, like Zhu Shilin’s 1961 adaptation of Cao Yu’s “Thunderstorm” -- the progressive studios also made genre films like Feng Huang’s tremendously expensive historical epic, The Golden Eagle (Chen Jingbo, 1964) or Great Wall’s wuxia classic The Jade Bow (Zhang XinYan, 1966). Painted Skin, a film from Feng Huang contract director Bao Fang, is itself a literary adaptation, but fits well with the previously mentioned films as a “soft film,” designed to entertain rather than instruct their audience.

The film frames the narrative as a story being told to Pu Songling. Pu authored the story collection, “Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio,” in the late seventeenth/early eighteenth century. Popular myth tells that Pu collected his stories from local passers-by and composed his collection out of their stories. There’s not much evidence to support this theory, but the film runs with it. It’s quaint and charming in equal measures.

Scholar Wong Chu Wen is an unsuccessful scholar studying to take the governmental exams in order to gain employment in lucrative administrative position. His brother advises him to forget about auspicious dates and omens and rely on his considerable knowledge of literature and history when he takes his exam -- a gentle way of saying “just study hard, you git.” All that goes out the window when a travelling Taoist tells him that success is in his future, and that to activate his good fortune, he should pray at an abandoned temple on his family’s property. Excited by this foretelling, Wong goes to the temple late at night, only to find a young lady. She tells him that she’s running away from an arranged marriage, set up by her cruel step mother, and that her father is a minister in charge of the examinations at the capital. Seeing this as an opportunity, Wong invites the girl, Mei-niang, to hide away in his study, and that he’ll take her with him to the capital.

He doesn’t tell his wife, or his mother, or his servants about Mei-niang and locks himself in his studio to “study,” spending days and nights there. He doesn’t tell Mei-niang about his wife. I trust the reader can see where this is headed.

Eventually, Mei-niang finds out about Hsia-ling, the scholar’s wife, and is incensed. She tells Wong that she thought that he would marry her once he earned a governmental position, but that now she has no chance at a socially advantageous marriage. Wong ruined her by ruining her.

To rectify the situation, Mei-niang decides that Wong should kill his wife, a task that Wong fails at completing. It is then that strange things start to happen at night, and an awful secret about Mei-niang comes to light.

Painted Skin works because outside of the opening scene, it avoids pedantry. “I know that you are using your tales of ghosts and demons to express your sense of justice,” is about as far in that direction as the opening with Pu Songling actually goes. The rest of the story slowly builds to the horrific reveal. Mei-niang is a ghostly spirit, and beautiful female ghosts and fox demons are well known as the natural predators of hapless scholars in medieval China. And while the film doesn’t follow every detail of the story, likely to avoid the disgusting sequence involving lots of (I’m not kidding) phlegm, it’s probably the most faithful cinematic recreation of one of the “Strange Tales...,” excusing its lapses in textual fidelity by framing it as the tall tale that eventually inspired the story that made it into Pu’s collection. Hence, Wong is really a complete dick, and it’s hard to feel bad for him. That’s about normal for many of the male protagonists in the “Strange Tales...”

As for how it is as a movie, Painted Skin exudes that classic glamour that makes golden age Hong Kong cinema so enjoyable. The way that the film fades out whenever something naughty is about to happen is utterly charming. It feels theatrical at times, with its long shots and careful staging, but isn’t un-cinematic. The moments leading up to the ghostly terror actually muster some real tension, and my only wish was that the film spent an extra ten minutes with its depiction of the supernatural. The simple make up effects and eerie atmosphere make for some effective moments of horror. But up until these moments, one unfamiliar with its source material might assume Painted Skin a very bleak period drama, rather than a horror-fantasy. And it’s a very good, if rather dated period drama up until that point.

An always thought provoking comparison is to look at stories that are frequently adapted as cinema and compare the treatment they receive in each decade or era. Comparing this restrained, conservative film with King Hu’s somewhat uncharacteristic adaptation from 1993 or Gordon Chan’s overproduced wuxia-grotesque from last year will probably give a very wrong impression of Hong Kong cinema’s progress. But it’s a fun time, and will provide an excuse to watch this quaint, sweet little ghost story.

Sounds interesting. The films of Feng Huang and Great Wall are unfortunately kind of a lost continent for viewers today. Is this one available on the grey market?

ReplyDeleteYou should be able to find it if you look hard enough. It was released on VHS, so there's also some avi copies floating about (Cinemageddon, if you're into that kind of stuff).

ReplyDeleteI think I saw the vhs on ebay or some other auction site once.

Thanks! I'll track it down. :)

ReplyDelete