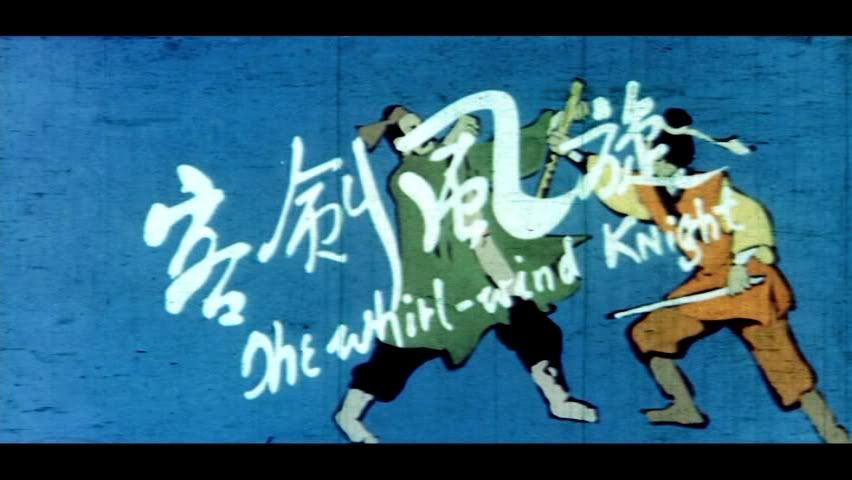

Whirlwind Knight reminded me of two things. The first thing was the way that Whirlwind Knight actually found itself onto a region 1 dvd, originating from a post on the Kung Fu Fandom message board. Somebody bought a truck load of film reels from Taiwan and wanted help selling them. If memory serves me correctly, the list of movies he posted had some comedies and melodramas, but most of them were either Taiwanese made wuxia films, period pieces, or ghost films. He originally wanted to sell them on eBay, but somebody quite rightly instructed him to contact potential distributors instead.

Not terribly long after that thread, Crash Cinema started announcing upcoming releases of rare films on their “Crash Masters” line. Some of them, like Flying Swordgirl, I had never heard of before, but a couple were highly sought after classics, like the Pan Lei/Jimmy Wang Yu wuxia-psychological drama, The Sword, which had circulated among collectors for years in a full screen, nth generation Korean VHS rip. Not long after that, a new company called Fusian, a division of Inspired Corporation, announced the dvd releases Taiwanese wuxia movies like Eight Immortals (Chan Hung Man), The Young Avengeress (Wong Cheuk-Hon, 1969) and King of Kings (Joseph Kuo, 1969). All of that resulted from a forum post.

Of course, none of the movies sold well enough to support Fusian or to keep the struggling Crash Cinema in business. Still, that was a nice time to be a fan and collector.

It’s interesting to actually see these films that Taiwan made in the wake of Shaw Brother’s “New Wuxia Century,” and the films of Chang Cheh and King Hu. On a narrative and thematic level, they’re far more conservative. Chang Cheh celebrated young rebels who decried the unfairness of the ancestor’s society -- a theme he continued in his youth dramas and contemporary crime films. And while King Hu certainly didn’t exhibit the same cheerful disregard for elders that Chang did, some cite him as a proto-feminist for his strong female characters that often exceed the bounds of what heroines are allowed to do in stories that follow more traditionally Confucian morality.

Whirlwind Knight tries to have it both ways. On the one hand, there is the titular knight that spends his time and skills as a swordsman attempting to build a living for himself and his estranged daughter, whose only real desire is to have her dad back in her life. He has the perfect opportunity to give up his roaming lifestyle and reunite with his daughter, but forgoes this chance in order to try and get a large sum of money out of the sadistic Golden Dragon Clan. In this story, the very Confucian value of familial loyalty is stressed, although it is a father, the paterfamilias, who has gone astray. Such a thing would be quite unusual in the more conservative wuxia films made by, say, Cathay. Nonetheless, things will eventually be set right by the end of the story, albeit after much death, the meddling of a masked bandit with exceptional martial arts, and the killing of a femme fatale in a manner too easily associated with these kinds of films -- the greatest and most punishable crime, it seems, is being a transgressive woman.

Although within the context of the narrative, she really does earn herself a killing. It’s a rather conventional, convoluted narrative.

The other thing that this movie reminded me of is Bells of Death. Yueh Feng’s spaghetti western styling affected not only the scoring and direction, but the fight scenes. Rather than following the lead of King Hu or Chang Cheh, the fight scenes in Bells of Death utilize all sorts of obtuse angles, camera work and editing. Basically, it looks like Yueh Feng wanted to shoot even his sword fights the way that Leone or Corbucci might. Now that I think about it, Pan Lei’s The Fastest Sword is similar in its experimentation. Rather than filming the fight scenes in the mid-length long shots that most others used, Pan shot the fights with lots of close ups and snappy editing that makes it look like a much more modern film than other 1960’s wuxia movies.

Whirlwind Knight has fairly standard fight choreography for 1969. Most of the fight scenes are well staged, but nothing special in terms of how they are filmed or edited. The lone exception is a fight scene in the middle of the film, taking place at night on a roof top. The most immediately striking thing about this scene is the copious reaction shots of the underlings as they get stabbed and slashed, culminating in a montage of bleeding mouths, horrified screams and death rattles. The timing is pretty rough and some of the shots would look better if they were better composed, but this could be a pretty gruesome scene in the hands of a more talented director/editor. The other thing that grabbed my attention was the lighting, which is heavily filtered with blue in the manner of Hong Kong movies from couple decades later. Isolated shots actually look like they could have come from a film made two decades later.

In spite of the rest of the film being statically filmed, under-budgeted, and stiffly acted, this particular scene is quite dynamic and shows a considerable amount of experimentation, just as Pan Lei and Yueh Feng did in their films. Such experimentation didn’t last, sadly. As kung fu movies began to dominate theaters, the camera work eventually began to standardize itself throughout the genre. Some directors still had their trademarks -- Chang Cheh punctuated his fight scenes with close ups and slow motion, usually for blood sprays; Chor Yuen filmed many of his fight scenes in long shots framed by foreground objects -- but by the seventies, fight scenes were always filmed in more or less the same manner. It makes sense, in that the sort of choreography that Hong Kong and Taiwanese film makers were famous for generally looked best when filmed in mid-length shots with minimal editing. But particularly with wuxia films, there are films throughout the seventies and eighties where cinema would have proven far more efficacious as a story telling device than kung fu. That is the reason why wuxia films like The Sword (Patrick Tam, 1980) and Duel to the Death (Ching Siu-Tung, 1983) were so much more effective, and seem so less dated, than some of their kung fu counterparts. While their competitors satisfied themelves with conventional approaches to film making -- often bad film making at that, either for lack of creativity or funding -- Patrick Tam, Tsui Hark, Ching Siu-Tung, Taylor Wong, and others attempted to make actual cinema, and found new methods of filming action sequences that are still emulated to this day.

When seeing some of the creativity that went into the Mandarin language wuxia films of this era, it really makes one wonder what the genre might have looked like if the people who made these films didn't have to reinvent the wheel every decade or so.

It was films like Whirlwind Knight about which Stephen Teo stated in Chinese Martial Arts Cinema: The Wuxia Tradition, “there is simply no critical impetus to study them due to long-held perceptions that they are too minor...” Truth be told, I disagree. Whirlwind Knight is no lost classic, but it is a fantastic tool for illustrating the weird evolution of a genre across language, national, and political barriers. Furthermore, it will probably entertain people who already enjoy these older films. It won’t be easy to come by for much longer; if you care, grab a copy before it sinks into obscurity again.

No comments:

Post a Comment